By Michael John Jaeger, volunteer docent

Over 700 aircraft models were certified in the United States during the 1920s and 30s. Some are still well known today, but most are forgotten to history. Many companies tried their hand in the aircraft business; some of their creations were good, some not so good. In addition, the Great Depression doomed lots of otherwise reasonable designs. In this article, we’ll look at an airplane that never even made it to certification.

90 YEARS AGO: The Ford Trimotor 14-A

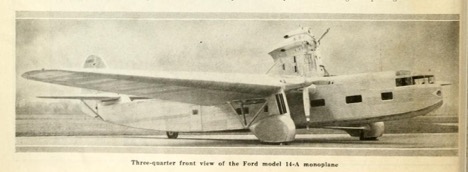

In the April 1932 issue of Aero Digest, an article called “The New Ford Air Liner” publicized Ford’s newest Tri-Motor design, the 14-A. The article states that “Its novel aerodynamic, mechanical and passenger-accommodation features make it outstanding in its class.” I think “truly bizarre” would be a better description.

From 1926 through 1933, Ford Motor Company built 199 Tri-Motors. Nicknamed the “Tin Goose,” the Tri-Motor was designed for airline travel. Produced primarily as models 4-AT and 5-AT, they featured a single wing, three engines, an enclosed cabin for up to 15 passengers, and, unusual for the time, an aluminum corrugated sheet-metal body and wings. The iconic Ford Tri-Motor was one of the first successful passenger airliners. The modern age of air travel had arrived.

What next? Bigger is better, so 1932 Ford cooked up the Model 14-A, with seating for up to 32 passengers. And what about comfort? The article states that the 14-A would “fulfill the needs of airlines for de luxe operation on trunk airways and cross-country routes, its comfortable accommodations rival the must luxurious forms of surface transportation.” Further, “Anticipating the requirements of night operations, sleeping accommodations comparable to those of the Pullman car are provided.” Ford was clearly trying to compete with the dominant railroad travel industry.

The Model 14-A might have luxury passenger accommodations, and for the early 1930s might have been considered stylish, but that styling has not aged well. To me it looks like something designed as a Tonka toy.

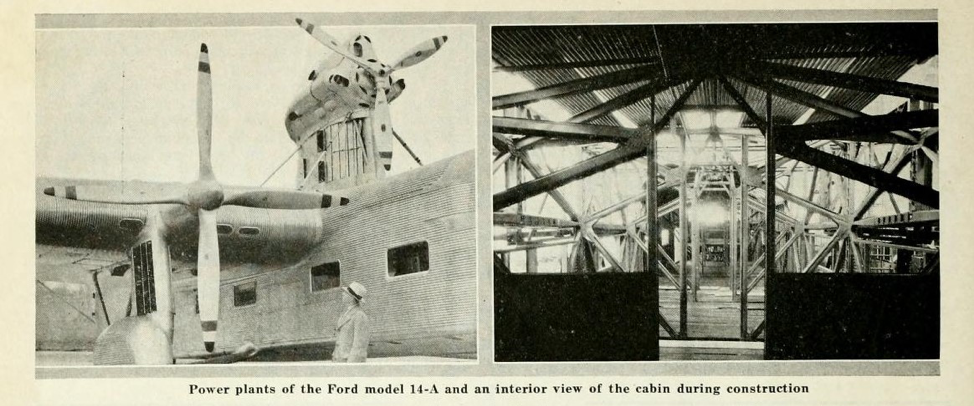

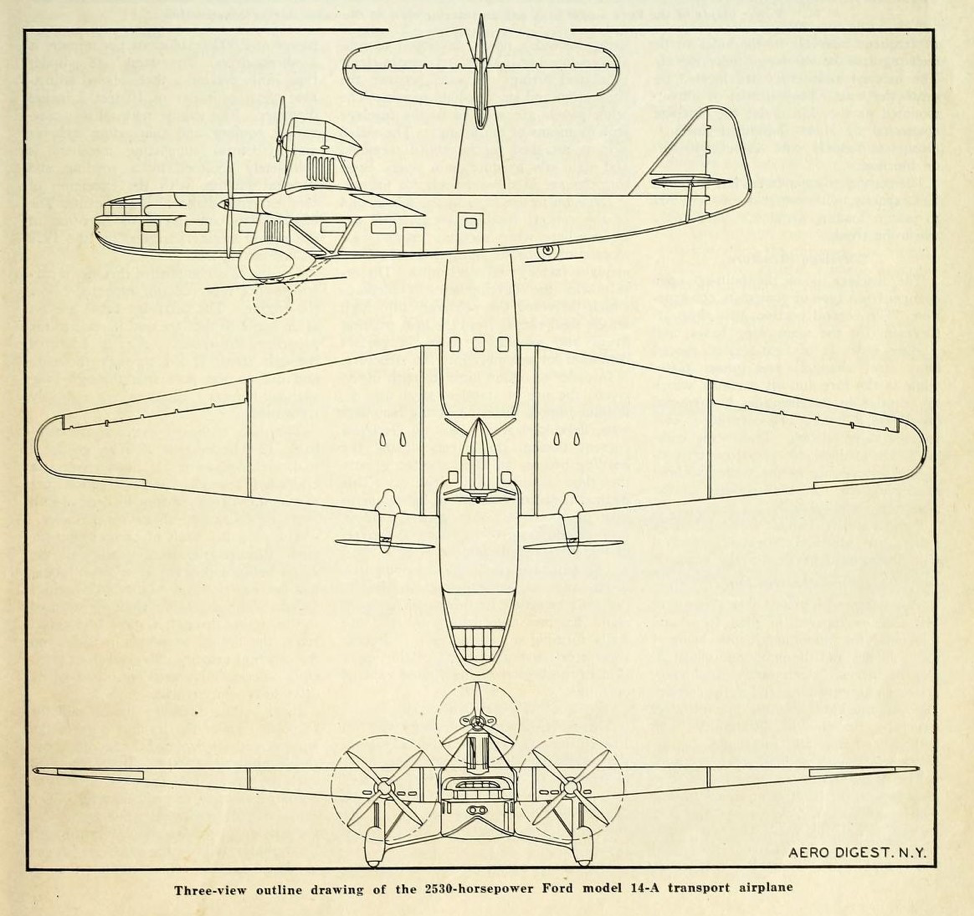

The 14-A’s engines totaled 2,530 horsepower, double that of the earlier Tri-Motors. The engine mounting was very unusual. The center engine, a Hispano-Suiza 1,100 horsepower 18-cylinder in a W-configuration, was mounted above the fuselage on a pedestal. The two outboard engines, both Hispano-Suiza 715 horsepower v-12s, were faired into the wing roots, with just the propeller shaft extending forward. These engine mountings in no way reflected the earlier Tri-Motor designs.

The cabin was over 41 feet long. Heading back from the pilot’s cockpit there was a smoking room, then four main passenger compartments, lavatories, a galley and baggage compartments. Eight Pullman-style seats converted into lower berths in the four main passenger compartments. The article stated that “For night travel, provision is made for installing upper berths at air depots as needed, eliminating the necessity for carrying this weight in daytime flying or at night when not required.”

The fuselage has a truss-type metal frame. Transverse bulkheads were needed for reinforcement of this truss. Central openings in the bulkheads allowed free movement through the length of the fuselage. These internal bulkheads, as shown in the attached photo, are likely why the cabin was laid out with multiple seating areas. Like earlier Tri-Motors models, corrugated aluminum sheets covered the entire aircraft.

The 14-A’s landing gear was very unusual, too. Fixed wheel fairings were mounted below the wings and braced with near-horizontal struts to the lower fuselage. The wheels themselves could retract into these fairings. On the ground the wheels were retracted into the fairings to lower the fuselage to the ground, resulting in a very low profile. Before take-off the wheels were extended, increasing the 14-A’s height by 4 ft 1 in, then retracted again in-flight to reduce drag.

All in all, a curious design. Was the Ford Model 14-A successful? No. Did it ever even get certified? No. In fact, it appears that the single prototype airframe never actually flew and was scrapped in 1933.

The architect Louis Sullivan’s famous axiom “form follows function” – the idea that the purpose of a building should be the starting point for its design – became the touchstone for many architects. One of his young associates, Frank Lloyd Wright, extended the teachings of his mentor by changing the phrase to “form and function are one.” I don’t think either had ever seen a Ford 14-A.

– Michael John Jaeger is a former pilot and avid trout fisherman. He can be found on Saturdays and Thursdays at the Kelch Aviation Museum, indulging his love for vintage aviation, magazines, and history. Stop by and visit him sometime!

Comment(1)

Tom Heitzman says:

May 11, 2022 at 8:51 pmReally enjoying watching growth & spread of the Kelch Museum. Here’s a Dropbox link to a really funky, scratch built model of that marvelous FORD that went up in flames! Say Hi to Pat & Kent!

https://www.dropbox.com/s/3v1ij6mdnzn7k78/1st%20FORD%20TRI.jpg?dl=0