By Michael John Jaeger, volunteer docent

The March 1932 issue of Aviation magazine is a mass of numbers and figures, in an attempt to portray the state of aviation at of the start of 1932. 39 pages of tables, graphs and text.

90 YEARS AGO: Illinois has more aviation than Wisconsin

The Kelch Museum is located near the Wisconsin-Illinois state line. In early 1932 there were 66 recognized airports in Wisconsin and 81 in Illinois – that’s 694 square miles per airport in Illinois, compared to 838 square miles per airport in Wisconsin. I expect this is mostly a function of Illinois’ greater population density.

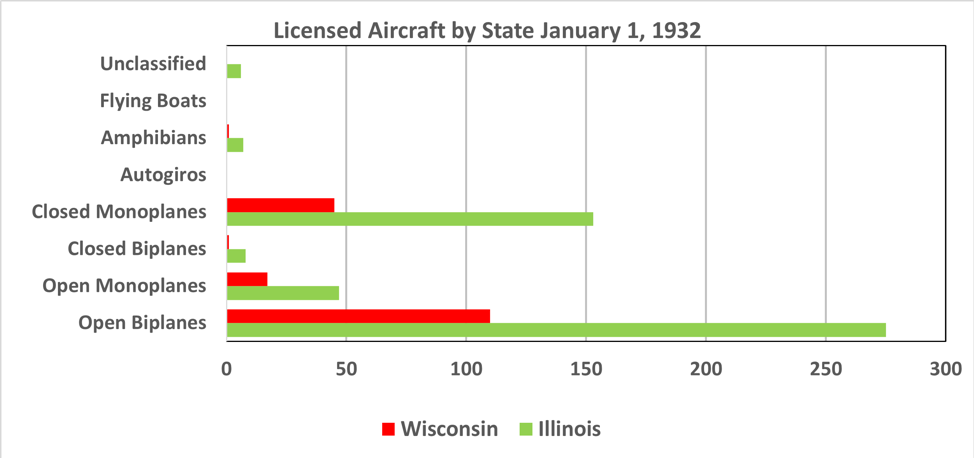

A similar pattern can be seen in overall numbers of licensed aircraft per state: 496 in Illinois and 174 in Wisconsin. It’s interesting to break down the numbers further, by aircraft type. Dominating in both states are open biplanes (55% in IL, 63% in WI); well behind come closed monoplanes (31% in IL, 26% in WI). I expect if I were to look up similar data for 1922 that the open biplane type would be almost universal.

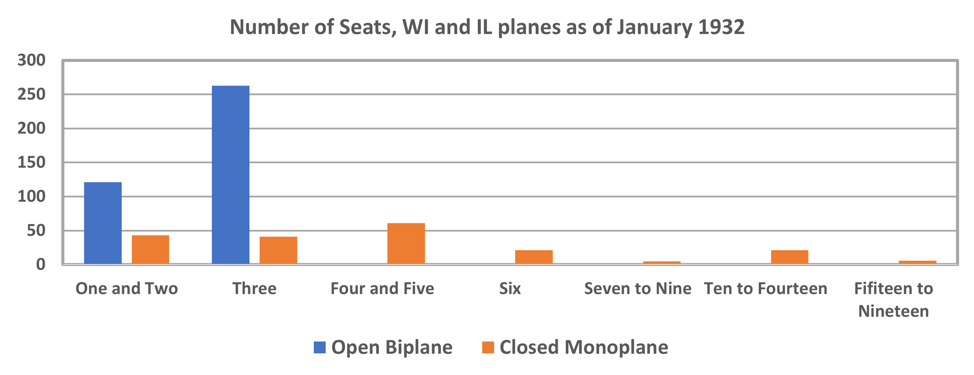

Diving further, let’s look at characteristics of those open biplane and closed monoplane numbers. My second graph shows the numbers of each type by their passenger capacity. In early 1932 planes of three or fewer seats were typically open biplanes, while closed cabin monoplanes made up almost all planes having four or more seats.

According to the text of one of the articles, the ownership levels at the beginning of 1932 “…shows conspicuous changes in the figures for three-seat open biplanes and three-seat cabin monoplanes, both of which show a very heavy shrinkage in the last year, and in two-place open monoplanes and four-place cabin ships, which have undergone notable increase.” This clearly reflects the overall Golden Age of Aviation: Biplanes dominated the early 20s, then single-winged aircraft and enclosed cabins rose to prominence as technology developed. The articles go on to say that the reduction of open biplane numbers is from the rapid recent elimination of three- to four-year old planes of this type, which were very popular in 1927 and 1928.

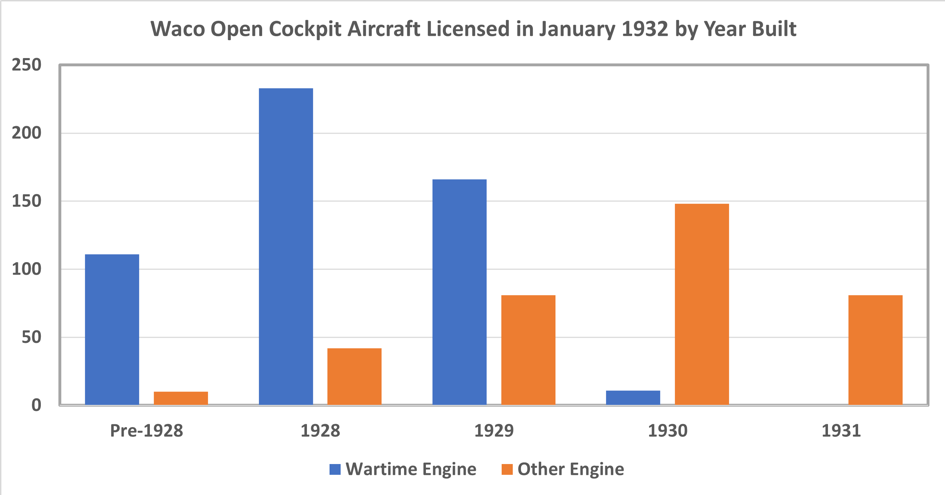

Then I stumbled across something unexpected. The articles also note that the drop in numbers of three-seat cabin aircraft represents the large pool of such planes with “wartime engines” built in 1929. “Wartime engines,” almost all water-cooled, were listed as Hispano, Liberty, OX5 and OXX6. While I couldn’t find figures in the March 1932 Aviation articles related to relative numbers of three-seat cabin aircraft with different engine types, there were relative numbers for Waco open-cockpit planes. I graphed the dramatic shift in the engine-type of U.S. licensed Wacos at the start of 1932. Of the 762 open-cockpit Wacos licensed at that time, 410 had wartime engines water-cooled engines and 352 were powered by something else. Even though the overall aircraft total numbers were similar, the 1928 and 1929 Wacos still in service were mostly powered by wartime engines – while those from 1930 and 1931 had other powerplants. A great example is the 1930 Waco RNF on display at Kelch featuring a non-wartime engine, a Warner Scarab radial.

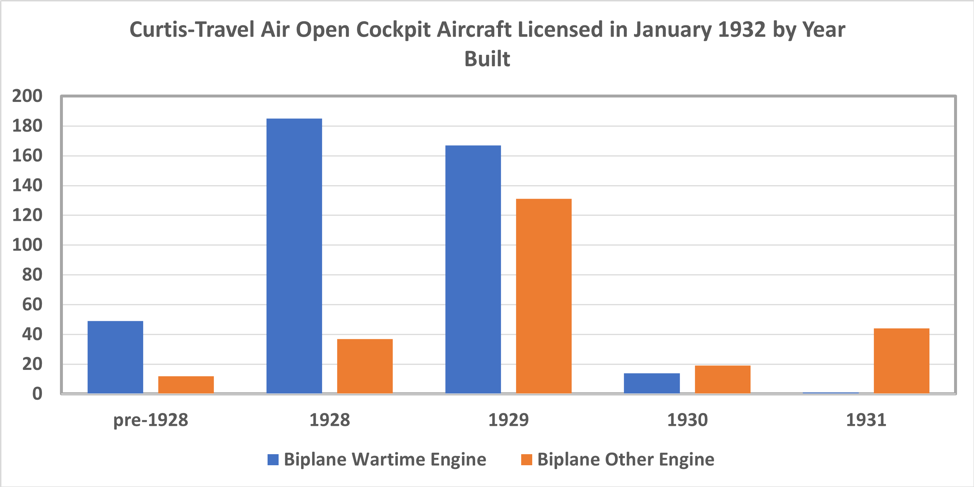

I then looked at similar data for U.S. Curtiss-Travel Air biplanes still licensed at the start of 1932 (the Curtiss Wright Corporation purchased the Travel Air Company in 1929, which is why their models are combined in this data). The planes they built up until 1928 predominantly used wartime water-cooled engines, while those built in 1929 were about an even mix of wartime and more modern engines. The two Travel Airs on display at the museum: The 1929 Model 2000 has a wartime water-cooled OXX-6 engine, while the 1927 Model 4000 has the new (in 1927) Wright Whirlwind J5 engine. By 1930, wartime engines on Curtis-Travel Air biplanes had become rare. Both early 1930s Curtis-Wright examples on display in the museum, the 12-Q and 12-W, reflect this change, with modern engines.

Why so many wartime engines?

At the end of World War I, large numbers of surplus wartime engines were sold for civilian use. These engines remained popular in civilian planes for at least ten years after the war, as my examples of the Waco and Curtis-Travel Air biplanes reflects. I wasn’t expecting this kind of story when I started out looking at the March 1932 issue of Aviation, but it clearly fits into the overall story of the Golden Age of Aviation. Illuminating, unexpected, and a window into the past: This is why I love paging through old airplane magazines!